The Black Lives Matter Movement raised some serious questions not only for America but all around the world. As a result, protests spread worldwide. This movement led me to think that maybe Turkey also hasn’t dealt with its past regarding minorities. That includes Black people living in the Ottoman Empire.

MY FIRST CONFRONTATION

It wasn’t until 2017 when I first started to think about Black culture in Ottoman and their history. The Istanbul Biennial hosted Fred Wilson’s Afro Kismet in Pera Museum that year. Its theme was “a good neighbor.”

According to the Biennal’s Exhibition book, “Wilson’s installation for the Istanbul Biennial includes a number of hand-crafted items related to Ottoman culture and black people’s roles within it. Black people have a long history in the region – many, if not most, with origins in the Ottoman slave trade – and today refer to themselves as Afro-Turks or Afro-Anatolians. Yet their presence has been incompletely recorded and acknowledged or misunderstood.”

Although Black people were servants in households or eunuchs (in Turkish, the terms used for Black women are “Arab sister,” “Arap bacı”) in the palace, the history of Black people in the Ottoman and Turkey is one of the issues that is never adequately addressed. (Also, it is not only discrimination against Black people but also Arabs.) Wilson’s installation has created a place of confrontation for me. Also, it was a starting point enabling me to notice the racist norms rooting in our culture. The same exhibit is still open to visiting the Gibbes Museum on workdays from 10.00 am to 5: 00 pm.

[su_youtube_advanced url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ppy731jX7yI”]

THE REPRESENTATION OF BLACK PEOPLE IN TURKISH CINEMA

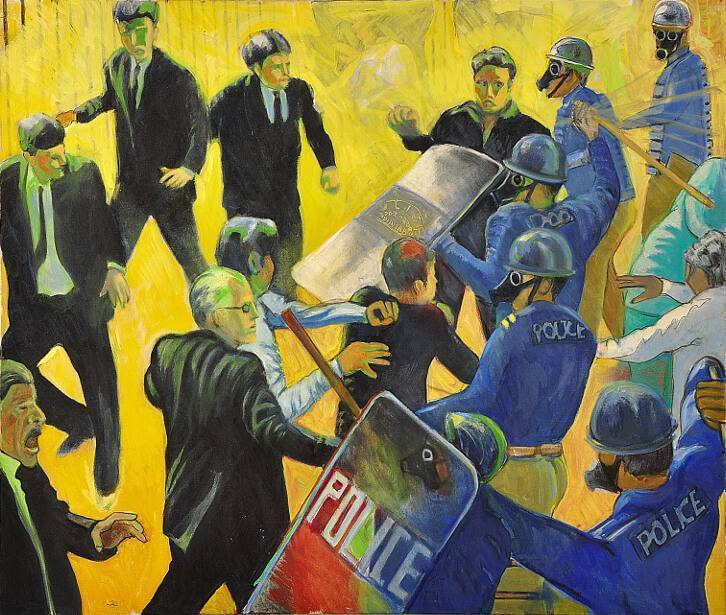

[su_image_carousel source=”media: 88825″ align=”center” captions=”yes”]

After #BLM protests during quarantine, I started to question how Turkish media, especially Turkish Cinema, represented Black people. Then it hit me: we raised with the images of “Arab sisters” portrayed as comic reliefs. Their accents were a comedic theme to make the audience laugh. For instance, in “Tosun Paşa” and “Süt Kardeşler” which we can consider them as cult films of Turkish Cinema during the Yeşilçam period; we watched a Black woman in the role of a servant or a nanny without noticing the power struggles and historical background behind this kind of a representation. Even today, we do not know the actress’ name despite other stars of the Yeşilçam era. However, Yasemin Esmergül played several roles in different movies, additionally to “Tosun Paşa” and “Süt Kardeşler”. She even sang for the film “Yalnızlar Rıhtımı.”

While searching about the Black people in Turkish Cinema and TV, I even encountered an advertisement of a well-known brand portraying a man who painted his face black, imitating an “Arab sister.”

Later, I found a small clip of a Turkish period show on one of the most-watched channels. Again, a lover was painting his face black to get closer to his beloved as acting as a nanny. The shocking part is this: that clip belonged only five years ago.

Since part of my family background has its roots in Turkey’s minority groups, I remember feeling repulsed seeing these representations, especially in movies that I saw when I was a child.

Thinking about how those images imposed into my mind in those early days scared me. Black people’s presence in Turkey and back in the Ottoman Empire’s days is an issue nobody talks about. Still, everybody secretly has some ideas imposed through our visual culture.

EVERYDAY RACISM

Later on, I started to contemplate some colloquial and cultural idioms we use frequently. For instance, we have a saying called “Arap saçına dönmek.” Its literal meaning is “turning into the hair of Arab.” Of course, that Arab image shaping in mind belongs no other than a Black person. This idiom indicates a situation turning into a conundrum.

[su_youtube_advanced url=”https://youtu.be/TjQH8smGzYk”]

Although people use this idiom often, I was never conscious of the representation behind it. One of the well-known Turkish rock music singers even has a song named “Arap saçı.” (Arab hair) If you’re not convinced about the assumptions and connections I made until now, I also learned that there is a plant named “Arap saçı” while writing this post, and I strongly suggest you take a look at how this plant looks!

“Arapsaçı” plant, means “Arab’s hair” because it looks like an Afro-hair

We can only understand how we learn to see by decoding these cultural stigmas. Until a couple of days ago, I wasn’t aware of how in our language, even color names are socially constructed depending on setting a “norm.” All those years, I used the term “ten rengi,” which means skin color, indicating a tone of beige. I didn’t even think about how this term could be racist.

Saying: “I’m not racist!” is easy, but while the system is racist and even our perception is shaped by racist norms, saying that is never enough. There is a widespread belief that Turkish people cannot be racist because no Black majority live in Turkey, and Turkish people are not white. However, even a little contemplation on our daily expressions reveals the racist way of thinking behind them.

To see the the Istanbul Biennal’s exhibition book: